The Anthropocene, a term widely discussed in environmental science, is often framed as a new geological epoch characterized by substantial human influence on Earth’s geology and ecosystems. Essentially, it marks a distinct departure from the Holocene, which has prevailed since the last Ice Age. The discourse surrounding the beginning of the Anthropocene has been contentious and layered, influenced by multiple factors, including industrialization, urbanization, and advances in technology. While scholars have proposed differing epochs as potential starting points, recent research led by a collaboration of esteemed Earth scientists points firmly towards the 1950s as the most compelling timeframe for this epochal transition.

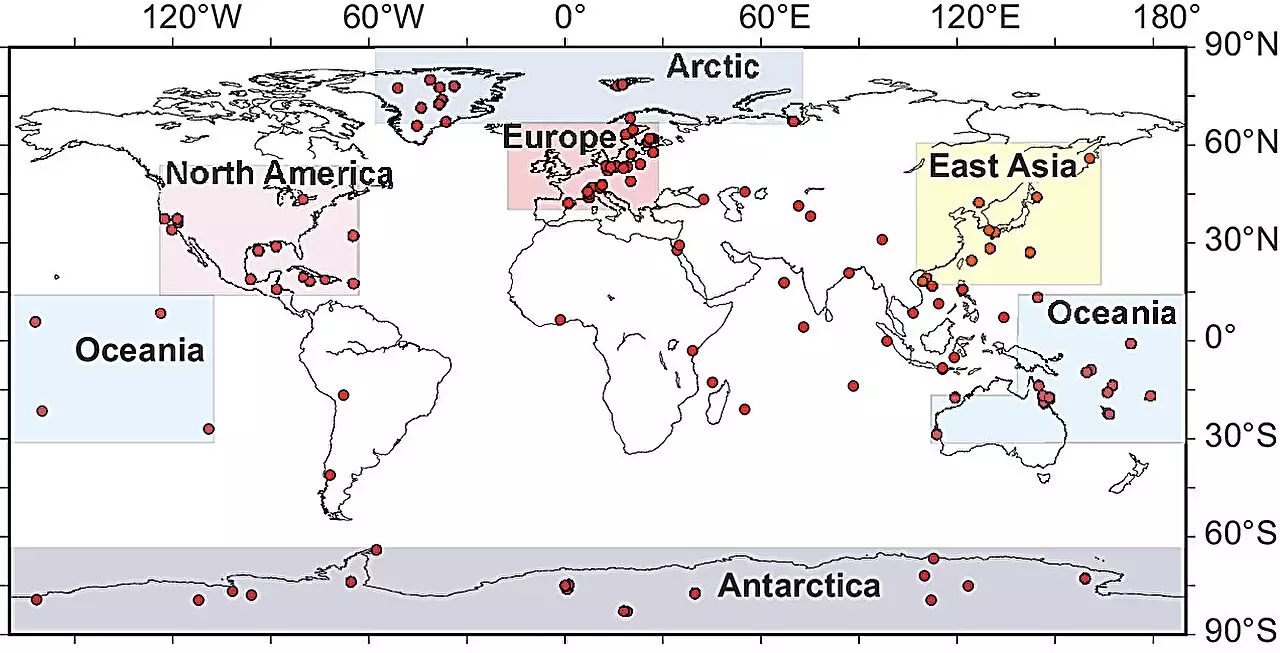

A collective of researchers from prestigious institutions such as the University of Tokyo and The Australian National University recently contributed to this ongoing debate through a paper published in the *Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences*. They contend that their fresh assessment of the Anthropocene supports the 1950s as the concrete starting point. This assertion is predicated upon a thorough evaluation of various candidates, which were narrowed down from earlier historical markers. The selection process involved comparing three distinct timeframes that harbored evidence of profound environmental change: the late 1800s, the early 1900s, and, importantly, the mid-20th century.

What distinguishes the 1950s from its predecessors is the scale and permanence of environmental changes that unfolded during this period. The scientists meticulously examined the unique markers of human influence, weighing metrics such as the proliferation of organic pollutants, increased plastic pollution, and the unmistakable vestiges of nuclear testing. The fallout from these activities left robust markers that can be detected globally, solidifying the argument for the mid-20th century as the pivotal juncture of change.

In their analysis, the researchers did not dismiss earlier epochs like the late 1800s or the early 1900s outright. They acknowledged the Industrial Revolution’s transformative role and the concurrent increases in lead levels and changes in stable isotope ratios. Moreover, the early 20th century saw significant shifts in ecological dynamics marked by alterations in pollen patterns and rising black carbon deposits. However, neither of these initial timeframes exhibited the same breadth and depth of change as the 1950s did.

The differences can be quantified and observed in the landscape itself. For instance, the proliferation of microplastics and other synthetic materials emerged as significant indicators of an environmental turning point. Additionally, the “nuclear age,” commencing in this decade, introduced further complications into Earth’s geochemistry, as the physical remnants of fallout became integrated into the global environment, thus solidifying the epoch’s hallmark characteristics.

Identifying the 1950s as the official start of the Anthropocene carries profound implications for our understanding of human-environment interaction. It serves as a crucial reminder of the extent to which human activity has irrevocably impacted the planet. Moreover, it raises pressing questions about responsibility, accountability, and action in the face of looming environmental crises, such as climate change and biodiversity loss.

The findings also challenge the prevailing narrative regarding the temporal separation of human actions from geological processes. By establishing a distinct marker for the Anthropocene, researchers advocate for the recognition of contemporary environmental issues as not merely routine variations in Earth’s history but as unprecedented shifts with lasting repercussions. Understanding that we are now shaping our planet in ways that were once unimaginable may provoke more urgent actions to mitigate these impacts.

As we navigate through the complexities of the Anthropocene epoch, recognizing the significance of the 1950s as a starting point underscores a critical point in humanity’s relationship with the planet. It invites an introspective examination of our collective role in causing irreversible changes to the Earth’s systems. Future discourse must not only celebrate the advancements that enabled such rapid change but also grapple with the responsibility we bear in curbing destructive behavior. The recognition of our impactful entry into this epoch should serve not merely as an academic observation but as a clarion call for conscious, sustainable living moving forward.

Leave a Reply