New research conducted by the University of Colorado Boulder has revealed a dire warning for the future of Antarctica’s coastal waters. The study projects that by the end of the century, the acidity of these waters could double, posing a significant threat to the diverse marine life that inhabits the Southern Ocean. Published in the journal Nature Communications, the researchers estimate that the upper 650 feet (200 meters) of the ocean, where much marine life resides, could experience a staggering increase of over 100% in acidity compared to levels seen in the 1990s.

The findings of this study hold pivotal importance in understanding the future well-being of marine ecosystems. The oceans act as a crucial buffer against climate change by absorbing nearly 30% of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. However, as more CO2 dissolves in the seawater, it becomes more acidic, primarily due to human-caused emissions. This process, known as ocean acidification, poses a significant threat to the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

The Southern Ocean, which surrounds Antarctica, is particularly susceptible to acidification. The colder water in this region has a higher capacity to absorb CO2, amplifying the effects of ocean acidification. Additionally, ocean currents in the area contribute to the relatively acidic water conditions. A computer model used by the researchers simulated the changes that would occur in the seawater of the Southern Ocean throughout the 21st century. The results indicated a substantial increase in acidity by 2100, with severe consequences if global emissions remain uncontrolled.

The Future of Antarctica’s Marine Protected Areas

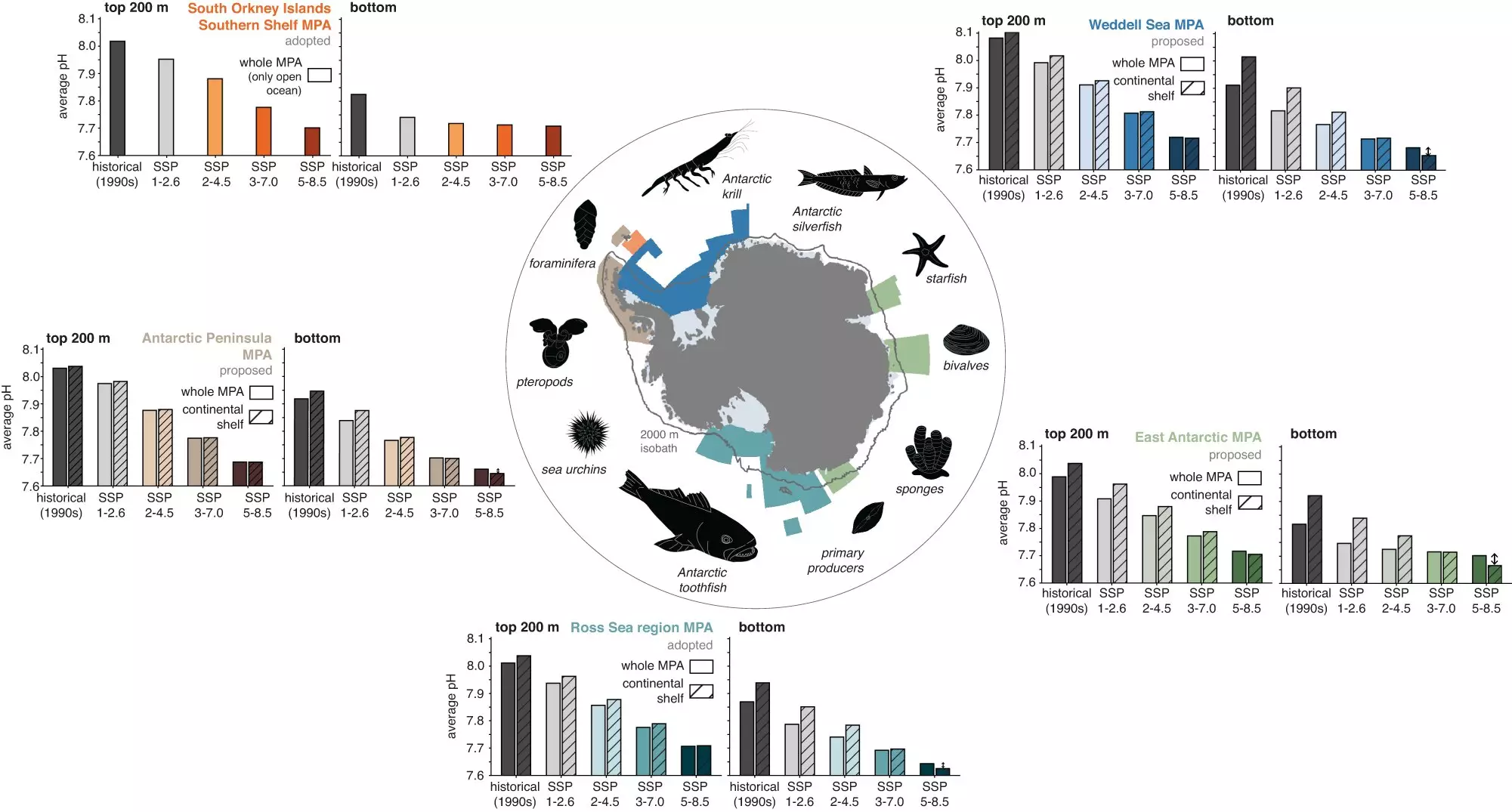

Antarctica’s marine protected areas (MPAs), where human activities such as fishing are restricted to protect biodiversity, were also investigated in the study. Currently, there are two designated MPAs in the Southern Ocean, covering approximately 12% of the region’s water. However, scientists have proposed three additional MPAs to an international council, which would encompass around 60% of the Antarctic Ocean.

The team’s model demonstrated that both the existing and proposed MPAs would experience significant acidification by the end of the century. In the worst-case scenario, where emissions are not reduced, the average acidity of the water in the Ross Sea region – the largest MPA off the northern tip of Antarctica – would increase by a staggering 104% compared to 1990s levels. Even under an intermediate emissions scenario, the water would become 43% more acidic. These projections reveal the alarming severity of ocean acidification in Antarctica’s coastal waters.

Previous studies have highlighted the harmful consequences of acidic waters on marine life. Phytoplankton, a vital group of algae that forms the basis of the marine food web, grow at a slower rate or die out when exposed to increasingly acidic conditions. Furthermore, acidic water weakens the shells of organisms such as sea snails and sea urchins, disrupting the delicate balance of the food web and ultimately impacting top predators such as whales and penguins.

One of the proposed MPAs, the Weddell Sea region, located off the coast of the Antarctic Peninsula, has been identified as a potential climate change sanctuary. Its high levels of sea ice coverage shield the ocean from warming and prevent the absorption of CO2, thereby reducing acidification rates. Moreover, the region currently has limited human activity. However, the researchers’ model predicts that as global warming continues, the sea ice will melt, leading to acidification levels comparable to other MPAs under intermediate to high emission scenarios, albeit with a slightly delayed progression.

This study highlights the urgent need for immediate action to protect Antarctica’s coastal waters. The projections underscore the severity of the acidification threat and call for substantial reductions in CO2 emissions. Only under the lowest emission scenario, where society rapidly and aggressively cuts emissions, can the Southern Ocean avoid severe acidification. The window of opportunity to select a responsible emission pathway is narrowing quickly. As researcher Cara Nissen emphasized, “We still have time to select our emission pathway, but we don’t have much.”

The impending increase in acidity in Antarctica’s coastal waters poses a significant threat to the Southern Ocean’s rich biodiversity. The research demands global efforts to reduce CO2 emissions and mitigate the impacts of ocean acidification. Urgent conservation measures are required to protect this fragile ecosystem for the well-being of marine life and the planet as a whole.

Leave a Reply