As human populations continue to expand and urbanize at an unprecedented rate, the issue of waste has become increasingly pressing. Waste, a natural by-product of life, has long been a challenge for living systems, but its impact on human systems has reached crisis levels. From microplastics infiltrating our bodies to wastewater polluting our waterways, and greenhouse gas emissions driving global climate change, waste poses a significant threat to our planet. Despite these alarming consequences, society often turns a blind eye to the unpleasant side of our production. Mingzhen Lu, an Assistant Professor at New York University, and SFI Professor Chris Kempes address this pressing concern in their paper published in Nature Cities, where they explore the production of waste as a function of urban systems.

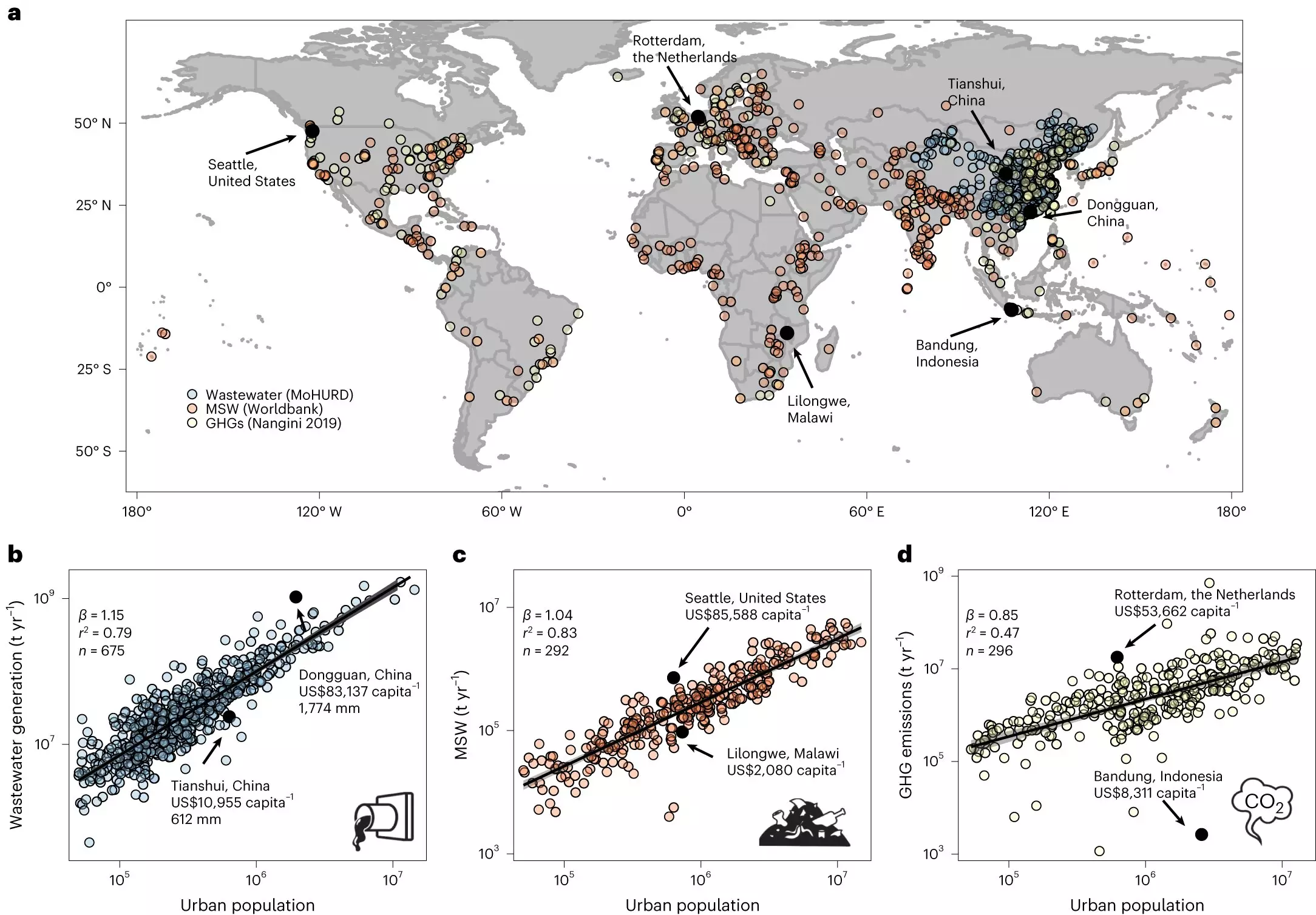

Lu and Kempes employ scaling theory, often used in biology to understand changes in organism physiology with body mass, to analyze waste production in over a thousand cities worldwide. By applying this theory, the authors extract patterns that show distinct differences in waste production as cities grow. Their study focuses on three key waste products: municipal solid waste, wastewater, and greenhouse gas emissions. The goal is to determine if waste production becomes more or less efficient as cities scale up and the burden of recycling that comes with it.

The results of their analysis reveal that waste production scales differently for each waste type. Solid waste, closely tied to individual consumption, scales linearly, increasing at the same rate as population growth. On the other hand, wastewater production scales superlinearly, meaning that larger cities contribute disproportionately more liquid waste compared to smaller cities. Interestingly, greenhouse gas emissions scale sub-linearly, indicating that bigger cities expel fewer greenhouse gases. This suggests an economy of scale for emissions, where growth brings more efficient energy and transportation infrastructure, but a diseconomy for liquid waste.

As cities grow wealthier, they tend to deviate from the universal scaling law. Cities with higher per-capita GDP generate more waste across the board, highlighting the strong link between waste generation and economic growth. The findings underscore the need for a new science of waste that can provide insights into the future state of urban ecosystems and inform policies to reduce waste and enhance sustainability.

Lu reflects on the remarkable capability of fungi to decompose lignin waste from trees and create sustainable ecosystems that have endured for millions of years. This observation emphasizes the importance of studying waste and finding innovative solutions to mitigate its impact on urban systems. By adopting a more comprehensive understanding of waste generation and its implications, policymakers and researchers can work towards a sustainable future that minimizes waste production and maximizes resource efficiency.

The mounting crisis of waste calls for immediate action. As urbanization continues to expand, waste generation has become a critical issue. Understanding how waste production scales with the growth of cities is vital for developing effective policies and interventions. The study by Lu and Kempes sheds light on the complex dynamics of waste and highlights the need for a science of waste to guide sustainable practices. By acknowledging and addressing the unpleasant side of production, we can pave the way for a healthier and more sustainable future.

Leave a Reply