Microplastic pollution is rapidly emerging as one of the most alarming threats to marine ecosystems. The issue is often conveyed through striking imagery of turtles ensnared in discarded fishing nets or seabirds with stomachs laden with plastic debris. Yet, the enormity of this crisis extends far beyond these compelling images. Annually, our oceans absorb roughly 12.7 million tons of plastic waste from both terrestrial and marine sources, including rivers, fishing operations, and shipping activities. However, the visible plastic waste that garners public attention represents only a fraction of the problem. The deeper issue lies in the microplastic sinks hidden beneath the ocean’s surface, which have gained increasing recognition in recent research.

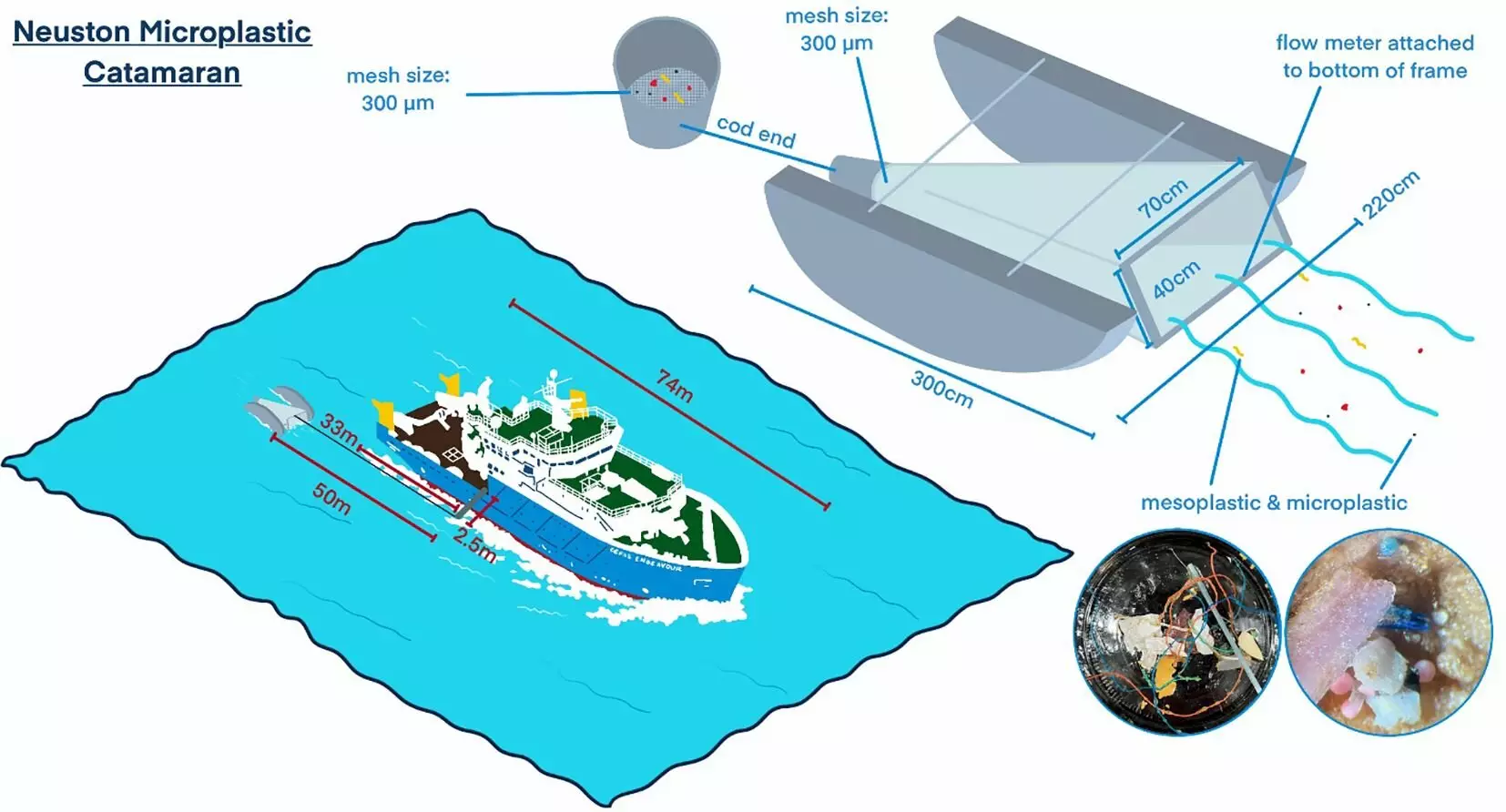

Recent studies, particularly one led by Dr. Danja Hoehn and her team at the Center for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science in the U.K., have provided insight into these elusive microplastic sinks. Using an advanced Neuston Microplastic Catamaran, the research team collected data from the North Sea in 2022. This vessel, equipped with a mechanical flowmeter and specialized mesh nets, is designed to capture microplastics lurking on the ocean’s surface—where they first enter from land or marine sources. Astonishingly, concentrations of microplastics peaked at over 25,000 items per square kilometer in the Southern Bight of the North Sea, significantly outpacing quantities observed in nearby offshore Scottish waters and Northeast Atlantic areas.

The composition of these microplastics sheds light on their origins and impacts. A staggering 67% of identified fragments were polyethylene, a common plastic found in shopping bags and children’s toys. Polypropylene and polystyrene followed with 16% and 8% respectively, further underscoring the varied uses of these materials, from packaging to textile production. Smaller pieces falling within the mesoplastic (5 to 25 mm) and macroplastic (over 25 mm) categories were less prevalent but still showed alarming presence. Notably, the enduring existence of microbeads—previously banned in the U.K.—highlights the transboundary nature of plastic pollution, suggesting ongoing transport via ocean currents from foreign sources.

The extensive study revealed a diverse array of plastic colors, with a notable dominance of white, often associated with plastic bags. Concentration hotspots were identified near the coast of East Anglia, reinforcing the idea that local environmental conditions can exacerbate the presence of microplastics. Despite these findings, the levels of pollution recorded in these U.K. waters remain strikingly lower than those documented in regions like the northwest coast of Spain and the Canary Islands, where concentrations soared into the hundreds of thousands per square kilometer.

This disparity raises questions about localized pollution management strategies and the effectiveness of national and international initiatives. Addressing plastic pollution is not merely a local concern but a global imperative that requires a coordinated effort across borders.

In response to this escalating crisis, several initiatives are underway. The U.K.’s Marine Strategy is developing a microplastic indicator for marine sediments, while the North-East Atlantic Environmental Strategy works to mitigate inputs of marine litter. Furthermore, the United Nations Environmental Agency aims for a legally binding resolution to eradicate plastic pollution by 2040. With global plastic production exceeding 400 million tons per annum, these commitments are increasingly urgent.

Strategies to mitigate plastic pollution must not only focus on the immediate impacts on marine life but also contemplate long-term ecological consequences. As microplastics continue to accumulate, their effects may permeate through the food web, posing health risks to both marine organisms and, ultimately, humans who consume seafood.

Microplastic pollution poses a significant threat to marine ecosystems that demands immediate action. As research underscores the complex dynamics of microplastic distribution and composition, it becomes clear that robust international cooperation and innovative policies are essential for effective management. As custodians of our planet, humanity must act decisively to stem the tide of plastic pollution—ensuring healthier oceans for generations to come. Understanding the intricate relationships and impacts of plastic contamination is paramount if we are to craft effective interventions. The time for change is now; our oceans and the life they sustain depend on it.

Leave a Reply